|

Back

Mr. Thoreau? Meet Mr. Beethoven New York

Isaac Stern Auditorium, Carnegie Hall

05/17/2013 -

Anton Webern: Passacaglia, Op. 1

Alban Berg: Three Fragments from Wozzeck

György Ligeti: Mysteries of the Macabre

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 6, "Pastoral", Op. 68

Barbara Hannigan (Soprano)

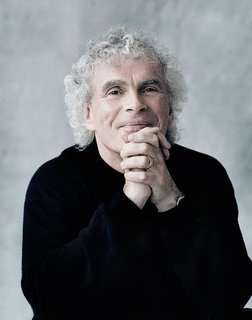

The Philadelphia Orchestra, Sir Simon Rattle (Conductor)

Sir S. Rattle (© www.simon-rattle.de)

Twenty-eight hours preceding this Philadelphia Orchestra concert, I had made a pilgrimage to Henry Thoreau’s Walden Pond, slowly circling the tranquil body of water over two miles of easy forest trails. So mellow, gentle and hallowed was this sauntering (Thoreau’s word) that I was consciously focused on nothing at all.

Over the last quarter mile, the appropriate stains did invade my mind, But those notes were decidedly not from the “Thoreau” movement–that tangled, gorgeous, atavistic, endlessly echoing Walden of Charles Ives’ “Concord” Sonata. Rather, Walden Pond generated in me a jaunty, simplistic, almost childish theme, the opening of Beethoven’s tone-poem, the Sixth Symphony.

Sir Simon Rattle filled in the rest last night.

Whether he meant to or not, Sir Simon led the Philadelphia Orchestra in three 20th Century preludes before returning to the straightforward look at Beethoven’s tribute to nature. Two of them looked back to the past–Webern’s homage to the 18th Century passacaglia, and Berg’s cracked mirror of 19th Century social injustice–and one look at pure surrealism, excerpts from Ligeti’s opera.

B. Hannigan (© www.barbarahannigan.com)

For a pair of these pieces, Barbara Hannigan was the astounding soprano soloist. One the one hand, it is almost unnerving to hear how her voice is pure pyrotechnical instrument. Perhaps only Ella Fitzgerald could reach the highest and lowest notes with every possible emotion, without a moment’s pause. Yet Ms. Hannigan, in the Ligeti Mysteries of the Macabre, has a range far greater than the divine Ms. Fitzgerald. Moreover, her sense of the absurd, both physical and vocal, outdid the work of any jazz artist.

Ms. Hannigan actually performed the entire Ligeti Le Grand Macabre under Alan Gilbert previously with the New York Philharmonic. It was a fabulous performance from both of them, albeit almost ruined by some off-putting puppets. Here, as she did several years ago, Ms. Hannigan had the stage to herself–so much to herself that she pushed Maestro Rattle off the dais to conduct the orchestra.

The last time, Ms. Hannigan looked like a crack-addled homeless crazy person. This time, she was simply a reckless madwoman, singing, strutting, dancing. It was all in absurd fun, of course, but with the addition of this voice, singing in unison with piccolo, timpani, and full orchestra, was one of those nine-minute events which could have gone on far longer.

The upsetting thing is that, had Ms. Hannigan sung a Liebestod or Schubert aria, the applause would have been merely polite. Here, she turned the house upside down.

Close enough to the Liebestod, though, were the three fragments from Berg’s Wozzeck, where Georg Büchner’s Woyzeck was turned into a cinematic series of scenes. Ms. Hannigan sung the poor Maria (as well as her child) with such acute intensity that one forgot Mr. Rattle’s huge orchestral resources. It was a vital vocal performance.

The opening work was a rare performance of a work on the very cusp of the 19th and 20th centuries. Anton Webern wrote his Opus 1 Passacaglia as a kind of exercise for Arnold Schoenberg, but the influences of other composers was so blatant. Not plagiarism at all, but this lush music with the huge Philadelphia Orchestra played the 23 variations with a color that could have come from Mahler, with a form like the finale of Brahms’ Fourth Symphony, and with such a mastery of the orchestra and form together that perhaps his genius needed to later pare it down to...well, to Webernian proportions.

This was the first time hearing it live, and Sir Simon gave it a dramatic import, enough retards to make it firmly in the Late Romantic tradition. It was huge in scope, but I doubt if Webern would have disowned such a work.

At the end, it was back to Beethoven, and his quote in the program notes which could indeed have come from Thoreau in Walden. “No one can love the country as much as I do,” wrote Beethoven in his journals. “For surely woods, trees and rocks produce the echo that man

desires to hear.”

The italics are mine. For both Thoreau and Beethoven were, on the surface, grouchy old misanthropes. Yet both of them, living within three decades of each other, needed to look at nature the way they could never look at “civilized” Mankind, whether in Vienna or Concord. And each somehow prayed that we humans might somehow find a balance for ourselves in this oh so bewildering universe.

Sir Simon gave a non-idiosyncratic reading, which did give a pictorial literalness to country dancing, birds and a great storm. But it was those outer movements showing the pristine loveliness of Nature where Sir Simon excelled. In the Philadelphia Orchestra, he had the winds (oh, what a clarinet!) and the strings to offer a peace out of place in our last turbulent century, yet offering the breadth and breaths of another era that, perhaps can only be found in music itself.

Harry Rolnick

|