|

Back

The Snow...er, The Show Must Go On New York

Theresa L. Kaufmann Concert Hall, 92nd St. Y

02/10/2010 -

Claude Debussy: En blanc et noir

Robert Schumann: Six pieces in Canonic Form, Opus 56 (arranged for two pianos by Claude Debussy)

Ludwig van Beethoven: Grosse Fuge for piano four hands, Opus 134

Igor Stravinsky: Agon for two pianos

Franz Schubert: Fantasie in F Minor for piano four hands, D. 940

Richard Goode, Jonathan Biss (pianos)

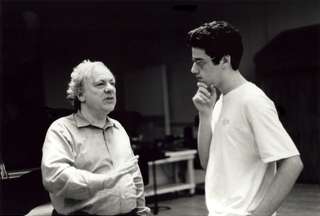

R. Goode and J. Biss (© Marlboro Festival)

New York’s blizzard might have closed down the public schools. But New York’s piano cognoscenti are not sixth-graders, and 92nd Street Y was almost filled for the rare appearance of Richard Goode and Jonathan Biss performing together.

They were not peas in a pod or Labèque Sisters. The two were utterly different. Mr. Goode is arguably the finest Beethoven pianist alive today, and he looks the part. The great sheaths of white hair atop a leonine head remind one (at a distance) of Franz Liszt. He is not stolid at the keyboard, not a Buddha-like Radu Lupu, but he is firm, steady, shows little emotion.

Mr. Biss, who gave his first New York recital at the Y nine years ago, has a burgeoning reputation for many composers, but his recordings of Schubert are amongst the finest of any younger pianist. He is lean, wiry, a wee bit geeky, but when he sways and bobs with the music, his movements have a rhythmic grace most unexpected.

What they have in common is a musicality formed of amazing talent, a joy in making music at the great Marlboro Festival (see picture above), and evidently an artistic relationship which leads to some singularly excellent playing. And they each played one of their “specials.”

The Beethoven was represented by the composer’s own four-hand version of his Grosse Fuge. It was played recently by some very adept pianists at Juilliard School, who used all the tremolos and martial spirit necessary for a satisfactory performance.

Goode and Bliss performed at two pianos, perhaps because Beethoven in his four-hand transposition had to alter the original music in order that the hands didn’t bump into each other. Obviously two pianos can give more space, less hazards.

The two pianists did not give a merely “satisfactory” rendition of Beethoven’s score. Rather, it was frightening, violent, more dissonant than most 20th Century works. I confess that at times, I had the idea that one of the two must be out of sync, missing some measures.

But I was wrong. These were Beethoven’s own discordant notes. In the quartet version, one knows that the notes are difficult, but one isn’t physically jarred by the sounds, since the different textures soften the blow. Last night, the two pianists played Beethoven the way James Levine performed the C Minor Symphony two weeks ago. This Beethoven was man of utter ferocity, utterly unafraid to wear his fierceness on his sleeve (or on his score).

This was a revelation of sorts. What I hadn’t expected was the revelation of Schubert’s very popular F Minor Fantasy. It is a difficult but hardly impossible work for two mediocre performers, since Schubert has such lovely tunes, even if they barely hang together.

Biss and Goode, though, gave it shape. That’s hardly easy after the composer’s sudden alterations, but they managed. The first theme, which returns so often, was not played as a song but as a slight, almost off-hand introduction. So each time it returned, they could change it, give it pulse, body, soften it. The stormy Allegro vivace had the form of a single symphonic movement, but when the storm-clouds departed, Goode and Biss offered that rare justifiable ending. Schubert, after all the changes, gave it chords which were actually liturgical. This time, those chords had meaning.

The evening opened, though, with Debussy’s late En Blanc et noir, based on the war paintings of Velasquez, and written during the Great War. It was a sure crowd-pleaser, as they dashed through the opening movement with all the energy needed. The despondent second movement and even the final Stravinsky-like dances couldn’t live up to that enthusiastic opening, but nobody fretted.

Two works were very rare. One, Debussy’s arrangement of some Schumann Canons. Perhaps Debussy added some octave unison notes or revised it another way. The depth of sound made it symphonic, but it seemed more an exercise than great composition.

That could hardly be said for Stravinsky’s own two-piano arrangement of his ballet Agon. Yes, technically it was hazardous, but in another way it was the most challenging work of all. The composer tried to replicate a few early 18th Century dances, so both pianists had to exactly coordinate the trills, sudden grace notes and subtle turns of phrase.

But this was where the two artists showed that, individual as they are, they share their values and their mutual love of the music. And not even the outside slush and snow and rain and puddles could sodden such wonderfully full-blooded playing.

Harry Rolnick

|