|

Back

The Voices of Spain New York

Stern Auditorium, Carnegie Hall

09/15/2022 -

Manuel de Falla: El Sombrero de tres picos: Suites 1 & 2 – Noches en los jardines de Espana – La vida breve: Interlude & Dance

Isaac Albéniz: Iberia Suite: 4. “El Puerto”, 1. “Evocación” & 3. “Triana” (Orchestrated by Enrique Fernández Arbós)

Amadeo Vives: Dona Francisquita: “Canción del ruisenor”

Pablo Sorozábal: La tabernera del puerto: “En un país de fábula”

Federico Chueca: El bateo: Prelude

Geronimo Giménez & Manuel Nieto: El barbero de Sevilla: “Me llaman la primorosa”

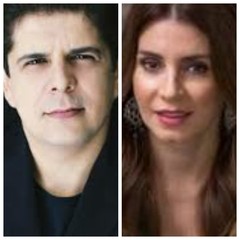

Sabina Puértolas (Soprano), Javier Perianes (Piano)

Orquesta Titular del Teatro Real, Juanjo Mena (Musical Director)

J. Mena (© Michal Novák)

“Every song is the remains of love. Every light the remains of time. A knot of time. And every sigh the remains of a cry.”

“The artist is always an anarchist in the best sense of the word. He must heed only the call that arises within him from three strong voices: the voice of death, with all its foreboding, the voice of love and the voice of art.”

Federico García Lorca

After 120 years, New York has finally caught up with one of the most exhilarating orchestras in the world. Last night, Orquesta Titular del Teatro Real (Madrid’s Royal Opera Orchestra) finally made its debut here. And while this ensemble, founded in 1903, has an international reputation (Prokofiev premiered his Second Violin Concerto with Royal Opera Orchestra), they wisely–brilliantly–played an all‑Spanish program.

Two of the composers are of course familiar here, though both de Falla and Albéniz worked most of their lives in France. Yet neither composer ever came near to hiding their Iberian ancestry. The other composers were part of the modern zarzuela movement, making use of that unique Spanish combination of drama, song, pathos, comedy and dance.

The latter, in fact, brought one of the most astonishingly ravishing soprano voices I’ve ever here. The first half, though, was for the familiar. And Musical Director Juanjo Mena rarely failed, though that first half rarely shoved the Spanish notes to Olé roars.

De Falla’s two suites from Three‑Cornered Hat, bookending the evening were vivid, clear, part lively, part laid back. One expected, after the joyous kettledrum/trumpet fanfare, to have a vocal answer by the Royal Opera Orchestra. Instead, the dances were presented as the orchestral masterpieces painted by the composer. Ending the concert, Mr. Mena played the Second Suite with far more zest. Not uninhibited, but an absolutely steamy “Miller’s Dance” and final “Jota.”

One needn’t wonder what this orchestra would do with Donizetti, Strauss, or Wagner, part of their operatic repertory this season. They had the brass, drums, fine woodwind soloists and strings for de Falla and Albéniz, and that was obviously sufficient.

In fact, their three selections from Iberia had a special link with the Royal Opera Orchestra. The orchestral arrangements were made by Enrique Fernández Arbós, himself a musical director of Royal Opera Orchestra for three decades. Again, while Albéniz’ Iberia was based on Spanish themes and dances, one felt here that most delicate–almost Ravelian–orchestration. Not so much played as painted by Mr. Mena.

I first heard de Falla’s Nights in The Gardens of Spain in the art gallery of Grenada’s Alhambra, surrounded by Spanish pastoral paintings. That left an impression so pictorial, that not even pianist Alicia de Larrocha could ever erase it. Javier Perianes knew that the work demands subtlety rather flashiness (the composer once said he hated pure technical prowess), so Mr. Perianes never overwhelmed his orchestra.

Rather than great digital proficiency, which he has, the de Falla was played with muted colors, with delicate weight, with nostalgia. Yes, the second movement danced, but it was the dance of 18th Century ballet, not Spanish gaudiness.

J. Perianes/S. Puértolas (© Igor Studio/Courtesy of the artist)

To this listener, the evening belonged above all–far above all–to operatic soprano Sabina Puértolas. I say “soprano”, yet this glorious singer could reach down to a mezzo’s dark range (oh, I wish she could play Carmen). Yet those were simply introductions. Ms. Puértolas’ range bedazzled the zarzuela arias reaching high and effortlessly to Empyrean high notes, she trilled and romped and–above all–was dramatically ravishing, both vocally and physically, while retaining, even above high C, a singular purity.

Oh, if I had my druthers, I’d give away any forthcoming concert to hear Ms. Puértolas do a full evening of bel canto and Spanish pieces together.

The evening was a joyous one, with a scintillating encore of a work by G. Giménez. Even more memorable was Ms. Puértolas’s encore. The Royal Opera Orchestra was lovely to hear, the works well chosen. But one could have experienced Ms. Puértolas’s voice, movement (and even her glistening chalk‑white gown) for many days to come.

Harry Rolnick

|