|

Back

O Death, Where Art Thy Strings? New York

Catacombs, Green-Wood Cemetery

10/08/2019 - & October 9, 10, 2019

Arvo Pärt: Fratres

Giovanni Batista Pergolesi: Stabat Mater

Samuel Barber: Adagio For Strings, Op. 11

Molly Netter (Soprano), Kate Maroney (Mezzo-soprano)

String Orchestra of Brooklyn, Eli Spindel (Conductor)

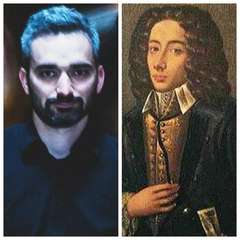

E. Spindel (taken in the Catacombs)/G. Pergolesi

(© Kevin Condon)

“...the most perfect and touching duet to come from the pen of any composer.”

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778), on the first movement of Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater

Rousseau, more than a philosopher, was something of a composer himself, his single opera owing much to Pergolesi’s comedies. comment of the Stabat Mater, heard last night appropriately enough in the Crypt of Green-Wood Cemetery was indeed right. The opening duet could rival anything in Rosenkavalier itself.

True, the rest of Pergolesi’s final work–written while he lay shivering to death at the age of 26–is hardly up to this opening. Yet is charmingt enough, with resources and duration minimal enough for any self-respecting 18th Century aristocrats to request it for their own obsequey.

This was the centerpiece of three works chosen by Andrew Ousley for his underground concerts. What fused the trio was not their doleful nature (the Pergolesi is rather jaunty), but that each piece was renowned in three different centuries.

Samuel Barber’s 1936 Adagio is now virtually a cliché for film background music and concert halls. Pergolesi was best known during his 18th Century for a few operas, but his 1736 Stabat Mater was sentimentally popular in the 19th Century. Perhaps as much for the composer’s early death as the music itself.

As for Arvo Pärt’s Fratres, our own century wouldn’t be the same without it.

Not even the Green-Wood Cemetery, where Fratres had been given an awesome arrangement just three weeks ago for cellist Joshua Roman and pianist Conor Hanick. That duo, in the reverberating atmosphere of the Catatcombs, didn’t simply offer the mystic modality of the original, the two artists became the sounds.

String Orchestra of Brooklyn members (© Kevin Condon)

The Strings of Brooklyn (which I dare not shorten with the initials of their name) simply could not replicate that duo. It wasn’t that conductor Eli Spindel led a poor ensemble, but that the aural power was divided. This is a lovely enough string ensemble, but the Pärt demands more, much more. It needs such perfect intonation that anything lesser–like a weak link for a precious necklace–can break up the so-fragile beauty.

Add to this two negative problems. Spotlights from the back of the Catacombs may have been constructed for special effects, but the off-and-on lighting was merely distracting. Then–and this was nobody’s fault–with a relatively large string orchestra, the drone from the lowest strings which should create a mood rather than a note, actually replicated an air-conditioner.

These problems didn’t interrupt a final work, Barber’s Adagio. The popularity has somewhat diminished its crescendo effects, the Late Romantic emotion appealing even to Toscanini. Yet the String Orchestra of Brooklyn played it well.

By far the longest work of the hour’s program was the Pergolesi. The charm may have lessened since its 19th Century apogee, probably because the world has embraced older more inventive artists, Bach, Monteverdi and their like. But this Stabat Mater can still make its mark.

Mr. Spindel led his string ensemble with a relatively zesty pace. The words and Pergolesi’s physical situation were both tragic, but the composer was a comic opera perfectionist, so one could easily translate the mawky rhymed 1849 translation into words for a bawdy tune. Yet soprano Molly Netter and contralto Kate Maroney were basically up to the operatic task. Ms. Netter was usually bright sometimes glaringly so. Ms. Maroney’s dark alto was effective in her solos.

But the grace of this Stabat Mater was not in those singular arias: it was in the duets. And these two melded well together.

In essence, I never quite felt what Mr. Ousley predicted was an evening to “grapple with the reality of grief.” Yet the Ineffable Spirit had indeed provided us a twilight to be relished by any painter, and a full moon to shed its reflected radiance on us all. And that, as the last word of the Stabat Mater said, “was sufficient.”

Harry Rolnick

|