|

Back

Images From The Depths New York

92nd Steet Y, Theresa L. Kaufmann Concert Hall

03/12/2019 -

Mieczyslaw Weinberg: Children’s Notebook, Book I, Opus 16 – String Trio, Opus 48 – Eight Preludes from 24 Preludes for Solo Cello, Opus 100 (Arranged for solo violin by Gidon Kremer) – Sonata for Violin and Piano No. 6, Opus 136bis

Robert Schumann: Bilder aus Osten, Opus 66 (Arranged by Friedrich Hermann)

Gidon Kremer and Sandro Kancheli: Images of the East

Georgijs Osokins (Pianist), Soloists from Kremerata Baltica: Dzeraldas Bidva, Dainius Puodziukas (Violins), Kristina Anuseviciūtė (Viola), Giedrė Dirvanauskaitė (Cello), Iurii Gavryliuk (Bass), Gidon Kremer (Violinist, Founder, Conductor), Kremerata Baltica

Nizar Ali Badr (Pebble Sculpture), Sandro Kancheli (Animator, Director, Images of the East), Clemency Burton-Hill (Moderator)

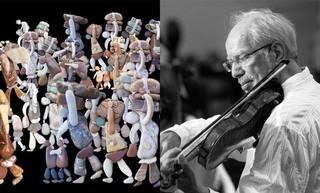

From Images of the East/G. Kremer (© 92nd Street Y)

“To reach people through the language…everyone understands: emotion. This I see as my obligation, my commitment, my calling.”

Gidon Kremer

Before reading another word, please visit this site. It is only four minutes of the 27-minute film shown last night at the 92st Y “Images of the East” concert with Gidon Kremer. Yet it does give a portion not only of a most remarkable sculptor, the Syrian “pebble artist”, Nizar Ali Badr. But also of the musical partnership 92st Y had tried to achieve with their “92Y Inflection Series”.

The goal is to bring together music with poetry, and/or painting etc. A few nights ago, Beethoven became intertangled with Wallace Stevens, with a confusing result. Last night, Gidon Kremer showed exactly how music and art can intertwine.

And in the process become humane, compassionate, and bring us, like Virgil brought Dante, to the darker side of humanity. In this case, it was the refugees of Syria. And in the animation by Sandro Kancheli and Nino Andriashvili, from some of Nizar Ali Badr’s 10,000-plus pebble-sculptors, one witnesses death and refugee boats, children and families, guns which commit screen-wide genocide, and shepherds with violins.

This with music played by Gidon Kremer and is Kremerata Baltica, an arrangement of Robert Schumann’s Pictures of the East and the Zodiac Box by Karlheinz Stockhausen. The film has no words, but the two groups of pictures are telling. First, first, the players of the Kremerata. More important, these stunning, tear-provoking images of the sculptures by multi-colored, multi-shaped pebbles, the natural elements of a beach in Latakia which I visited many decades ago.

At that time, the site along the Mediterranean was as idyllic as any town in Greece or Turkey. Later, the Russians built their huge base, destroying most of the beach. Today, Latakia has been almost bombed out of existence.

And Nizar Ali Badr? He continues working. But with no glue available in Syria, he can only make his sculptures, photograph them....and let them float back to the eternity from which they came. Along with the inspiration (and I would imagine much-needed funds) to help him survive in this, one of the multitude of living hells in the world.

M. Weinberg

92nd St Y is one of New York’s redoubtable institutions, but in this case, by failing to provide program notes on the composer of the first half, and his chamber music, they lost a great opportunity. Mieczyslaw Weinberg was more than an intensely interesting composer. He too was a victim of political crises, of prejudice of a man without a country. Going from Poland to Russia, losing his entire family in the Holocaust, he is a man whose sorrows never overpowered his music, but were part of it.

His friendship of Shostakovich was legendary, yet perhaps his musical similarity put him in the shadows. Not that Weinberg worried about that. In fact, one of the solo Cello Preludes was an exact imitation–call it very conscious plagiarism–of Shostakovich.

In a certain way, Gidon Kremer’s transcriptions of the Preludes was disappointing, since Weinberg’s own cello works were so brilliant. The opening measures of the Cello Concerto are easily among the most beautiful in all cello literature. On the other hand, Mr. Kremer’s performances from eight of the original 24 was another dazzling Kremer experience. He worked his way through Weinberg’s sarcasm, his glowing slow Prelude, that Shostakovich rewrite, and more. Wonderful stuff.

As were the other chamber works, which I had not heard before. Such as the opening Children’s Notebook works, played deftly by Georgijs Osokins. Perhaps Weinberg’s problem was that his language was spoken on the cusp of other composers. These pieces were engaging (and far too difficult for children), but they echoed Janácek and Prokofiev and of course Shostakovich.

The Trio was played beautifully, but it was the strange Sonata for Violin and Piano which gave the picture of Weinberg and the whole meaning of the concert. It started with a dissonant, desolate cadenza by Mr. Kremer, continued with more spiky sounds, and ended with a bareness, a bleakness...

Weinberg had written this after learning the fate of his family. What choice did he have–what choice does Nizar Ali Badr have?–than to paint his feelings with his art? Not to offer naked tears, not to mask the emotions. But to to exercise their creative souls and offer the tactile results to dtheir listeners.

Harry Rolnick

|