|

Back

The Elation of Romantic Madness New York

Isaac Stern Auditorium Carnegie Hall

10/15/2018 - & October 12, 2018 (Ann Arbor)

Hector Berlioz: Symphonie fantastique, Opus 14 – Lélio, ou Le Retour à la vie, Opus 14b

Simon Callow (Narrator), Michael Spryes (Tenor), Ashley Riches (Bass-baritone)

National Youth Choir of Scotland, Christopher Bell (Artistic Director), Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique, John Eliot Gardiner (Founder, Artistic Director, Conductor)

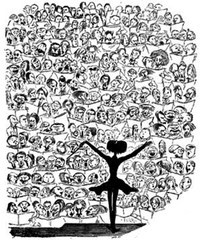

J.-E. Gardiner leading his orchestra

“To render my works properly requires a combination of extreme precision and irresistible verve, a regulated vehemence, a dreamy tenderness, and an almost morbid melancholy.”

Hector Berlioz

During twenty seconds in Hector Berlioz’ Lélio last night, the heavens of the Hereafter seemed to descend upon Carnegie Hall. The spotlight was on narrator Simon Callow, the rest of the stage dark. The light broadened, the upstage piano played soft chords, continuing with the strings, tenor Michael Spryes was singing, and the entire National Youth Choir of Scotland softly began singing the exquisite song of the fisherman.

Lélio had other moments–many other moments, of rapture, passion, martial airs, even Callow’s humor at times. Yet that single moment was the divine gem radiating over the entire work.

Rarely performed, never heard in New York, Lélio is a secret gem. The rarity is not simply for the large ensembles: full orchestra, full choir, piano, tenor, baritone, narrator, all of whom have to be top-rate. But Lélio is also, let’s face it, a structural mess.

Yes, the Narrator, waking after his opium nightmare in Symphnonie Fantastique, gives a patina of structure. He is that arch-Romantic Hector Berlioz himelf (who wrote the narration), pining for lost love, dreaming of Shakespeare (Berlioz couldn’t speak English, but translations were many) and dying a thousand deaths, like a French Werther.

Between his melancholy, though, Berlioz inserted songs and choruses. Some from early works, some original, some themes from the earlier Symphonie fantastique itself. They don’t make much sense on paper–but to the ears, the narration (beautifully uttered and acted by the venerable Mr. Callow), the piano, the gorgeous subtle orchestration (until the last blasting section), the choruses, all offer a myriad of what might be called “The Best of Unknown Berlioz”.

And even those of us familiar with the songs and choruses in other settings were stunned by the total tapestry in Mr. Gardiner’s production here. After the conductor’s performance of Ulysses last year, I vowed to hear his every showing in New York, whether it be Monteverdi or Bach or Berlioz or anything else.

M. Spyres/S. Callow

Nor did he fail here. This was more than a concert production. Mr. Callow narrated and spoke with the conductor, he was the picture of the 19th Century tragic hero. Mr. Spryes, well worth his estimable reputation, was the Hero doppelgänger in his arias (dressed nattily in 19th Century duds), and baritone Ashley Riches gave splendid singing.

The drama was in the lighting and acting. And when the lads of the National Youth Choir of Scotland leaped up and pummeled each other for the Song of the Brigands, one didn’t regret this to be a vrtual repeat of the student song from Damnation de Faust. It was great theater for incredibly great music.

I used to think that my ultimate Berlioz “moment” was Seiji Ozawa conducting the Tuba Mirum from Requiem, summoning voices from every balcony in the Hong Kong Cultural Center. For sheer unexpected beauty, though, John Eliot Gardiner is a more than worthy contender.

Gustave Doré, Journal pour rire (1850): H. Berlioz leading his orchestra

This was the second half of an all-Berlioz concert (and foolish be those who left in the interval). Due to hearing AXIOM and Louis Andriessen’s De Staat, the day before, I couldn’t hear the Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique’s first Berlioz concert.

The opening Symphonie fanatastique gave an indication what I had missed. The ensemble is basically a middle-ground between “ye ancient consorts” and today’s modern orchestra. Outside of some shaky horn playing (were these valveless horns?), the vision of a prehistorical ophicleide and, what looked like a serpent, as well as electronic bells, it could have been a fair-to-middling ensemble of today.

What stood out were not the mediocre sounds which probably reflected Berlioz’ own, but Mr. Gardiner’s whiplash conducting. Urgent, spot-on, he retained that electric, sometimes feverish tension, even in the meandering “Country” movement. Bringing on four harps for the “Ball” broke up the work a bit, but the four women in the front of the stage at least gave an illusion of a ballroom.

Mr. Gardiner knew above all, that this was not a Richard Strauss picture-book turn-the-page-for-the-next-chapter work. This was a pre-Freudian study of obsession, hallucination, suicide, and Symphonie fantastique was the demonic side of Coleridge’s “Kublai Khan” opium dream, and Mr. Gardiner injected his orchestra with every nuance of madness.

Were this a therapy chamber, he would be damned for malpractice. In the Carnegie Hall auditorium, his genius, both for the well-known opener and its rare remarkable sequel, Lélio, he deserves a Berlioz Hosanna for a endless Berlioz orchestra and chorus.

Harry Rolnick

|