|

Back

The Inner Life of the Pampered Prodigy New York

Grace Rainey Rogers Auditorium, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

05/22/2016 -

“Sight and Sound” “Mendelssohn, Turner and Romantic Imagination”

Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy: Symphony No. 3 in A minor, “Scottish”, Opus 56

Artwork: Joseph Mallard William Turner’s Whalers and others

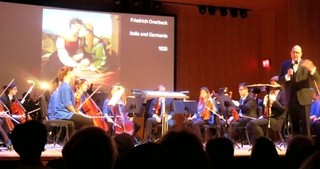

The Orchestra Now (TON), Leon Botstein (Founder, Conductor, Lecturer)

TON Orchestra, L. Botstein (© Samuel A. Dog)

All too late, I realized it was a mistake to attend Leon Botstein’s lecture at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Mendelssohn, Turner and Romantic Imagination”.

The error was that I had recently finished writing program notes on a Mendelssohn symphony for an overseas orchestra, being certain to include all the platitudes, anodynes and musical analgesics about the composer. My assured picture of Mendelssohn showed him as the pampered prodigy, the prodigious fluent, close-to-classical perfectionist.

And within 30 seconds of Leon Botstein’s pre-Symphony lecture, I discovered that I had been entirely off the mark.

Which meant re-writing my annotations, and roundly cursing Dr. (Maestro? Professor?) Botstein for his infernally brilliant knowledge.

That cognition and the revolutionary results, though, we will get to later, since the initial reason I was lured from a somnolent Sunday afternoon was not Leon Botstein. It wasn’t his new TON Orchestra or Felix Mendelssohn or the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Instead, I was seduced by memories of British director Mike Leigh, whose 2015 film Mr. Turner was a passionate portrait of the mid-19th Century landscape painter. Mr. Leigh’s understanding of art was embraced in a movie of such human verisimilitude that I had no choice yesterday afternoon but to hear a talk and listen to the “Scotch” Symphony which apparently augmented Leigh’s faultless film.

True enough, in Mr. Turner, Mr. Leigh eschewed filming in the actual Scotland, where Turner painted The Whalers. Yet why should he have bothered about the “real thing” when W.J. Turner was bent on improving reality? Why worry about Mother Nature and her minute-to-minute vagaries? W.J. Turner could–like Joshua’s plea to God–make time stand still!

So Mr Leigh was my prime mover this afternoon. But Leon Botstein hardly played second fiddle (In fact, he would be a commanding Concertmaster.) Not primarily as a competent conductor, but as a scholar of inexhaustible knowledge and a thinker who is able to relate–no, to interjoin, interrelate–trends, facts, eras, art and people into essays which are not only perspicacious in facts, but enlightening in history.

I am sometimes reluctant to attend his three-hour-long concerts, but always eager to read his notes. Without saying so, Mr. Botstein implies, unlike Hamlet, that the times are never out of joint, that far-reaching linkages can be truly lucid. And this was how he started and continued his pre-concert.

With the screened background of German and English paintings of the early 19th Century, Leon Botstein destroyed all those idyllic images we have of Mendelssohn shmoozing with Queen Victoria and dancing in Dresden. He, in fact, turned the composer into a man who embraced the giant legends of his day, who–like Turner’s picture–was intent on showing tiny Man and gigantic Nature together on one symphonic slate.

In one of his countless letters, Mendelssohn said that “art and life are not two different things.” Life, though, as Mr. Botstein affirmed, was not the biographical life of this scion from one of Germany’s prime intellectual and financial families. It was the inner life of Mendelssohn, the creative life of a man whose drafts and paintings (shown on the screen), his letters, his prejudices (he didn’t want the equally talented sister to publish her music) and of course his music which reflected the composer.

Mr. Botstein didn’t need any notes. He understood and elucidated the early 19th Century German idealizations which confronted Man and Nature. Endless pictures of men and mountains, castles and palaces set amidst the wildest scenery. Through the picture Italia and Germania, he showed how the Teutonic mentality felt it must be paired with the Italian Renaissance.

Mr. Botstein’s talk was encompassing, yes, though he omitted certain literary aspects of the German mentality. Without mentioning the name Byron, he showed Byronic landscapes, those of Harold in Italy. He produced a picture of Tintern Abbey with its great columns, without mentioning Wordsworth’s ode to that medieval structure.

Nor did he mention the burgeoning German racism set amidst the monumental pictures. How they had “cleaned up” the Semitic features of Jesus, making him an Aryan hero. How the linguistic studies of the Grimm Brothers had led to the German nationalism which produced Wagner and finally Hitler.

Turner’s Whalers (© Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Of course this Germanic artistic strain influenced England as well. (Though not, thankfully the xenophobia.) So we had the epic grandeur of “Mr. Turner”, his whalers, his great splotches of the sea. Mr. Botstein brought in Ossian, the supposed ancient epic writer, whose work was actually written by James Macpherson–and, with Sir Walter Scott, was one of the great influences of Mendelssohn.

So now we come to the composer. How the name “Bartholdy” was tacked on to show the Jewish-born composer was actually an Aryan. Unlike those other “converted” secular Jews, Mahler and Schoenberg, Mendelssohn apparently didn’t fret over his heritage (both Saint Paul and Elijah were tributes to his pair of religions). Instead, as Mr. Botstein showed with musical examples, he was fascinated by the Gothic architecture of Scotland and Germany, by the brave doings of the mythical Ossian, and above all, by the ghostly ruins of Holyrood Palace and the other sites of history.

Mr. Botstein hinted at the early 19th Century artistic rebellion against the “arrogance of reason”, and blatantly affirmed that Mendelssohn’s symphonic creations were the musical reproductions of painting’s perspective and texture, as well as the Myth of the Hero.

That, though, would come later with Schumann and Wagner. For after an intermission, the The Orchestra Now (badly re-affirmed in the jeu de bruit “TON”) gave a pleasant enough performance of Mendelssohn’s most extended homage to his very mythical Scotland.

It shouldn’t have been merely “pleasant”, but after our discourse on the heroic Mendelssohn, the recently created TON is hardly up to the heroic sounds of the composer. Yes, the ghostly introduction, the wondrous Adagio and that most majestic final theme coming up from the underground of French horns, were impressive enough. But they hardly had the loftiness with which Mr. Botstein had cloaked the composer.

One more minor sin of omission. That old question about the output of Mozart, Schubert and Mendelssohn, had they lived beyond their 30-plus years, would be beyond his orbit. But Mendelssohn’s blessed life in Europe’s blessed era came to a chronological end in 1847–and Europe’s placid life came to its own end with the political riots of 1848, events which still shake the world today.

Wagner altered his own musical views after that event, and one wonders whether Mendelssohn would have come off his lofty post of Heroes and Nature, to embrace the new rebellious proletariat. There is obviously no answer to that. But Mr. Botstein’s cognitive hypotheses would sure inspire those insights he gave yesterday.

Harry Rolnick

|