|

Back

The Agony and Ecstasy of Musical Secrets New York

David Geffen Hall, Lincoln Center

04/27/2016 - & April 28, 29, 30, 2016

Franck Krawczyk: Après (World Premiere)

Robert Schumann: Cello Concerto in A minor, Opus 129

Johannes Brahms: Symphony No. 2 in D Major, Opus 73

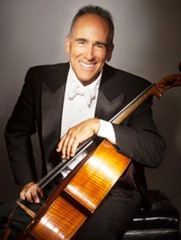

Carter Brey (Cello)

New York Philharmonic Orchestra, Alan Gilbert (Music Director/Conductor)

F. Krawczyk (© Cultureboxfrancetvinfo)

“The past is, for me, like a punctured memory in which oblivion interests me as much as memory.”

Franck Krawczyk, as quoted by Frank J. Oteri

Frank Krawczyk, whose Après (New York Philharmonic Commission, with the support of the Kravis Prize for New Music) was given its world premiere last night, has a paradoxical way of verbally explaining his music. Not only the quote above from the Phil’s Playbill, but his unorthodox enigmas about the music. The French title meaning not only “after” but “taking after”, as “bringing to mind”. A first movement entitled “Coda”. Another, with vague Beethoven quotes called “Reconstitution”. And a career which started when he jumped off a piano seat during a recital of the Pathétique because “Beethoven gave me the power to interrupt my own concert.”

Whew! (Or perhaps “Huh?”)

The French composer has not, to my knowledge, been heard in New York before, and on YouTube, all I found were choral arrangements, almost Mantovani-style, of Chopin and Vivaldi’s Winter.

Still, if he was praised by the late Henri Dutilleux, this was enough for great curiosity. Outside of the laborious titles e.g. II. Reconstitution (Hommage à L.van Beethoven) (pour György Kurtág), the 18-minute piece started with a sumptuous highly romantic section for high strings, based on a string quartet he had written. This Barber-like ode was interrupted at times by burps in the brass, which might have justified the direction in the score: “Applause for the Obsequies”. (These quotes come from the program notes.)

That was indeed both sparkling and glowing. It was followed by various sections mainly for brass and winds, these the nebulous quotes from Beethoven. Not, thank heavens, one of those “let’s-be-clever” bricolages, but something so subtle and nuanced that it did appear as memory rather than repetition.

Still, while Mr. Krawczyk obviously knows how to make some wonderful orchestral effects, I frankly never found a single structural cusp or phrase or repetition upon which I could grip.

Some have compared parts of Krawczyk to Webern, but one senses in Webern (even if one doesn’t feel it) fractional connections, metamorphoses of phrases. Perhaps they existed in Après, but they were hidden behind the orchestral colors.

The last movement was enigmatic, but extremely appealing. A short piano phrase, almost doubled by harp. This followed by orchestra, then repeated again.

And while the entire work left me cold, these evasive moments breathed a sincerity, a desire to achieve an all-too-secret musical truth.

C. Brey (© NY Philharmonic)

If Franck Krawczyk gave us a mystery, conductor Alan Gilbert and First Chair Cellist Carter Brey succeeded in opening the Schumann Cello Concerto with an equally mysterious (though rarely undiscernable) neglected masterpiece.

True enough, the Schumann isn’t anywhere near the more open, even flamboyant Elgar and Dvorák (though parts of the second movement seem to have been lifted by Elgar). But Carter Brey is one of the treasures of the New York Philharmonic. One of those rare artists who have used their fame as a soloist to lift up the full cello consort in the orchestra.

What that meant here was a communication which overcame the inevitable heaviness of Schumann’s orchestra. (Oh, what a heavenly Concerto this would be with truncated orchestral forces.) Mr. Brey’s first long long declaming of the cello was a personal introduction rather than a stolid proclamation. In fact, Mr. Brey never played this first movement as either virtuoso vehicle or earnest oratory. Schumann, he might have felt, was in a wonderful mood when he wrote this, and the soloist should share in this joy of inspiration.

That second movement showed, ironically, what Mr. Brey has done with the NY Phil cello section. His duet with second-chair cellist Eileen Moon was tender, and the whole movement with its rising Elgar-like interval, was truly touching.

Mr. Brey’s whole attitude to his instrument and the orchestra (at times he was paying far more attention to the ensemble than Mr. Gilbert) was so graceful that the jovial finale was not a break from the first sections. The orchestral interplay was clear, the tempos were lighthearted, and Mr. Brey’s cadenza was not a flaunting of his powers, but another touching set of ideas.

The Schumann is decidedly a technical challenge, yet Mr. Brey is the kind of artist who resolved to give it ideas and inspiration.

Alan Gilbert devoted the second half to another work of poetry, Brahms’ Second Symphony. Simultaneously, it was another tribute to Carter Brey, whose cellos opened the Adagio non troppo with understated ecstasy.

For such a sunlit work, Mr. Gilbert started rather heavily, I felt, but by the second movement, aided by aforesaid cellos, and a wonderful horn solo by Philip Myers), he had brought the Phil into a mellow phasis. That remained on point all the way to a finale which, while never overbearing, possessed an unadulterated grandeur.

Harry Rolnick

|