|

Back

The Triumph of Music New York

Isaac Stern Auditorium, Carnegie Hall

04/20/2016 - & April 17, 2016 (Chicago)

Dmitri Shostakovich: Symphony No. 7 in C Major (“Leningrad”), Opus 60

Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, Mariss Jansons (Chief Conductor)

M. Jansons (© Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra)

The greatest affront against Dmitri Shostakovich’s “Leningrad” Symphony is not that it’s propaganda or bluster or bombast or third-rate. That can be taken in its stride. No, the most wicked words about the music is that it has a hidden anti-Soviet, anti-Stalinist message.

That musical palimpsest, issued by Solomon Volkov, goes against everything we know about the composer. True, the Stalin-Shostakovich relationship was complex, and true, as we know from Brian Moynihan’s harrowing book, Leningrad: Siege and Symphony, published two years ago, Stalin’s paranoia during the Second World War was psychotic. True, Shostakovich wrote some wickedly abusive pieces about Stalin.

Yet above anything, Shostakovich was a patriot, an almost mystical lover of Mother Russia. And his Seventh Symphony had no esoteric messages. His pictures were undeniably the steps of the Nazis violating the beauty of Russia, his further movements were images of fighting and resolution. And the final dazzling C Major chord has no secret contents. It was the ultimate victory of Russia against the Barbarians.

Mr. Moynihan’s book makes that transparently clear. And Mariss Jansons’ performances of this “Leningrad” with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, itself created just seven years after the composition, was the literal triumph of Shostakovich’s literal story.

Yes, it was propaganda, yes, it could be blustery enough that even Béla Bartók parodied it. But nothing in Shostakovich is third-rate. It is the voice of the composer, the inner Muse (not the man who wrote it in a comfortable dacha a thousand miles from the fighting). And whether or not we approve it, there is no way to denigrate its meaning.

One could also insult the composer by saying that only a Russian orchestra could perform this. No, Shostakovich wrote for the world, and the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, led by a Latvian who had studied in Leningrad, was its very prime mover.

I had never heard them play live before, so cannot compare Mariss Jansons’ leadership with others. Yet this was an orchestra all of whose consorts played with flair, and whose ensemble gave an unending lift to these 75 minutes.

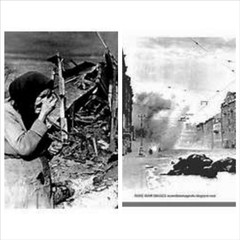

Leningrad at war

Dedicated to “the heroic defenders of Leningrad, to the Red Army and to our victory”, this may have been propaganda, but under Mr. Janson’s baton, one needn’t have been aware of that. It is nice to know that the “Eroica” was about Napoleon. But it is still the “Eroica”, had it been dedicated to the life of a caterpillar.

Mr. Jansons began with sturdy confidence, the oboe theme played with tough woodwind flair. And when he came to the most famous moment of any Shostakovich symphony, the inanely-named “Bolero” theme, the orchestra gave a rare magnificent performance.

Rare in that this Ravel-like crescendo was more than a crescendo. It was a series of variations which were never abrasive or crude. Rather, he led the orchestra onto various hues, combinations, with that goofy rhythmic background, and ironic oboe theme at the end. If this was bombast, let the bombast continue!

And now one must ask in that “first-movement finale”, what does a conductor do with three more movements. Mr. Jansons answered with warmth and glory. The two “lyrical intermezzos” gave those lustrous violins time to shine, the segueing themes (in an admittedly bulky symphony) were given inevitable transitions, the care of each instrument gave a gripping intensive to each measure.

In the first and last movements, Shostakovich shamelessly quoted from Mahler. And in that finale, that was perfectly appropriate. Nobody ever accused Mahler of “propaganda”: it was inspired music. Shostakovich here, gave honor also to his past other melodies in this symphony, and–like Mahler teasing us before a great climax–Shostakovich finally brought forth that final chord with all the shimmering power of the Bavarian orchestra.

Obviously no encores here. But Mr. Jansons made virtually every First Chair and Ensemble stand individually. He had no choice. In a challenge taken by few, he had come out both victorious and exalting.

Harry Rolnick

|