|

Back

05/18/2019

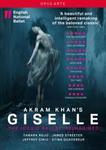

Giselle

Akram Kahn (choreographer), Adolphe Adam (arr. Vincenzo Lamagna) (music)

Tamara Rojo (Giselle), James Streeter (Albrecht), Jeffrey Cirio (Hilarion), Stina Quagebeur (Myrtha, Queen of the Wilis), Begona Cao (Bathilde), Fabian Reimair (Landlord), Jung Ah Choi, Adela Ramírez, María José Sadles (Giselle’s friends), English National Ballet and Philharmonic, Gavin Sutherland (conductor), Tamara Rojo (artistic director), Tim Yip (set and costume designer), Mark Henderson (lighting designer), Yvonne Gilbert (sound designer), Robb MacGibbon (screen director)

Recording: Liverpool Empire Theater, Liverpool, England (October 28, 2017) – 125’ (including bonus)

Opus Arte OA 1284D (or Blu-ray BD 7254D) – LPCM 2.0 and DTS Master Audio 5.1 – All regions (Distributed by Naxos of America) – Booklet in English

Giselle is among a handful of classical ballets from the 19th century that enjoys revivals by companies all over the world. It themes trendy among younger audiences, owing to its gothic themes, not to mention those fearless phantom brides, the Wilis, who, in the afterlife exact justice on wayward men. Most ballet companies stick to its original 1841 choreography by Jean Coralli and Jules Perrot, and the later improvements made by Russia’s Imperial Ballet choreographer Marius Petipa in the 1880s. Now, British choreographer Akram Khan has completely re-imagined Giselle for the English National Ballet (ENB). In a word, it is a ballet knockout, visually and choreographically, as danced by the full ENB Company with an electrifying new score by Italian composer Vincenzo Lamagna. Fortunately, the production was filmed in 2017 for broadcast, masterfully directed for the screen by Ross MacGibbon and now released on DVD and Blu-ray by Opus Arte.

Set in the brutal early industrial British towns of the late 19th century where workers labor under brutal conditions, Kahn’s ballet is just as much about oppressed masses as it is about doomed lovers. The set and costume design by Tim Yip create an industrial factory England of the early 20th century, among them the Outcasts in bowler hats and the women in raggy work clothes, in contrast to the wealthy landlords who appear in futuristic Elizabethan drag. A shrieking siren, right of an Orwellian nightmare, summons the factory workers in the regimental ensemble in front of a prison wall with disturbing markings.

Kahn’s choreography for the Outcasts is post-modern fusion with various styles of cultural dance. The ensemble passages as much physical theater. The ensemble building is a communal language with thrilling feral leaps and gallops, quotes from highland jigs and dramatic communal dances. It is a gushing choreographic stream that is full of evocative sensibilities, a jarring surreal dance template showcasing Kahn’s artistry with potent choreographic storytelling.

In the original ballet, the plot point lumbers as through narrative pantomime acting. In Kahn’s version, the exposition is in the characterizations of Giselle and her suitors Hilarion and Albrecht, and the full-on dancing by the corps de ballet that is just as much a part of the story. Kahn’s contemporary vernacular is often fused with various disciplines of Kathak classical disciplines of Northern India. Giselle is no longer the fragile virginal lass of a 19th century maiden en pointe. She is part of a physically brutal world, and she has the steel to resist unwanted control. She is attached to Hilarion, but she is also falling in love with Albrecht who is traveling incognito. When Hilarion exposes him as part of the aristocracy, things get emotionally raw. Hilarion and Albrecht fight in the town square, but when Albrecht’s royal relatives appear, he pushes Giselle away and returns to Bathilde at the insistence of his rich family.

Giselle collapses after she realizes that Albrecht shuns her, and Giselle lays lifeless on the ground when Myrtha, the Queen of the Wilis, appears who, drags her body into the factory ghost world behind the wall and initiates her into the covenant of the Wilis. Hilarion, danced with equal measures of wit and menace by Jeffrey Cirio, is the lothario and trickster who can move in both the privileged and the Outcast worlds. The character is rough with Giselle and instead of recoiling, she pushes back at his control. Myrtha summons the Wilis out of the darkness in their ragged antique dresses and brandishing sticks, or clamps them in their mouths in menacing rituals. Hilarion descends into this world and tries to see Giselle, but Myrtha stops him and the Wilis exact their revenge.

Hilarion descends behind the wall to the ghost world and tries to capture Giselle again. Rojo goes into a fury of pirouette runs until she spins into his arms. The Wilis encircle Hilarion and trap him with their sticks (a scene reminiscent of Robbins’ The Cage.) Hilarion tries to climb out, but he falls back into the rabble. Even with all this movement drama, it is hard to take your eyes off of Stina Quagebeur as Myrtha, her minimalistic pointe work is hypnotic.

Albrecht appears and Myrtha confronts him. She commands Giselle to pierce him with the stick, but Giselle refuses and Myrtha backs down. Like the original story, he feels her presence but does not see her. And like the original, Kahn choreographs one of the most intimately romantic pas de deux for their phantom reunion.

Kahn’s brutish characterization of Hilarion is powerfully communicated by Jeffrey Cirio...his magnetic physicality just explodes during his air-slicing jumps and classical variations. Kahn choreographs very lyrical passages for James Streeter’s Albrecht, like a true romantic, but when he casts off Giselle, he is the lyrically tragic fallen hero. Tamara Rojo, former star of the Royal Ballet and now director of the English National Ballet, entrances as an earthier, but luminously ethereal Giselle. Akram Kahn’s technical requirements of Giselle are at least as equal to the pyrotechnics of the classical vocabulary when she danced as Principal at the Royal Ballet. Throughout, Vincenzo Lamagna’s score is as progressive as Kahn’s choreography, most notably when he laces in central melodies from Adolphe Adams’ original score.

Lewis J. Whittington

|