|

Back

08/16/2018

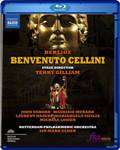

Hector Berlioz: Benvenuto Cellini

John Osborn (Benvenuto Cellini), Mariangela Sicilia (Teresa), Maurizio Muraro (Giacomo Balducci), Michèle Losier (Ascanio), Laurent Naouri (Fieramosca), Orlin Anastassov (Pope Clement VII), Nicky Spence (Francesco), Scott Connor (Bernardino), André Morsch (Pompeo), Marcel Beekman (Le Cabaretier), Chorus of the Dutch National Opera, Ching-Lien Wu (chorus master), Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra, Sir Mark Elder (conductor), Terry Gilliam (stage director, stage co-designer), Aaron Marsden (stage co-designer), Katrina Lindsay (costume designer), Leah Hausman (co-director and choreographer), Paule Constable (lighting designer), François Roussillon (film director)

Recording: Dutch National Opera, Amsterdam, The Netherlands (May 15 and 18, 2015) – 180’

1 Blu-ray disc Naxos NBD0074V – Booklet in English only – Subtitles in French, English, German, Korean and Japanese

This production contains such a quantity of outright craziness that many will find it simply goes too far. It certainly brims with entertainment, starting with titles featuring a collage of images much like those its director Terry Gilliam created for the Monty Python television show and films.

The historical Benvenuto Cellini led a notoriously eventful life (he probably murdered four people but this was not the main focus of his activities.) He always managed to regain the protection of powerful people so he could continue his artistic endeavours. He also wrote a self-serving autobiography which served to inspire the scenario for this opera, although its events are pretty much all fictional.

The libretto inspired Hector Berlioz (yet another artist with a vivid sense of life and drama), and for this production Terry Gilliam, renowned for his unique sense of absurdity, has further accelerated the action. Examples: where the libretto calls for the apparent doubling of characters he triples them. A group of women who occasionally figure in the action are played by men. The Roman Carnival scene features a scurrilous lampooning of Cellini that could have come from the fertile mind of Pietro Aretino (a large cucumber figures in the action.)

The plot centers on the familiar trope of young lovers trying to outwit a controlling oldster, in this case the father of the young woman. The papal treasurer Giacomo Balducci has a 17-year-old daughter, Teresa, who has managed to fall in love with the sculptor Benvenuto Cellini (and he with her), though her father wants her to marry another sculptor, Fieramosca, who is no slouch himself in the scheme-concocting department. The pope has commissioned a work from Cellini and demands to see the results (Cellini has already spent the money.)< br/>

In the carnival mêlée Cellini has managed to murder one Pompeo, a cohort of Fieramosca’s, and he could be hanged for this. To the dismay of Balducci and Fieramosca, he manages the seemingly impossible feat. (I have simplified the plot; there is a lot of running about, and one must pay close attention.)

The lengthy overture is accompanied by a lively stage action which serves to give us a clear introduction to the various characters; this is a real help given the welter of activity to ensue. One of the features of the work is that the overture (and later Roman Carnival music) are the most memorable parts of the score despite the presence of some nice arias, especially for the title character in which John Osborn does a terrific job. Cellini is portrayed as a shambling, ultra-bohemian 40-something (thus not exactly a young lover, and an unlikely object of affection for a young girl), and the fact that Teresa is 17 gives him the image of an old lecher. However, when he has close-ups for his ardent arias, he has the look of sweet innocence that anyone would welcome as a son-in-law.

All the roles are well cast. Mariangela Sicilia amuses as Teresa, maintaining a look of sweet innocence despite her character’s headstrong machinations. Michèle Losier as Ascanio, Cellini’s assistant, steals every scene she appears in, and her moments with Cellini foreshadow the Hoffmann-Nicklausse relationship in Offenbach’s fevered masterpiece. Orlin Anastassov, as the pope (supposedly Clement VII but who cares), has a shock-and-awe entrance outfitted as some sot of Hindu deity; at first he is rather distant from the microphones, but he eventually makes a good aural impact.

The score is notorious in having even more intricacies than the plot; the Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra, under the guidance of Sir Mark Elder, is close to awe-inspiring.

The one flaw is that the action flags toward the end. Act III wraps things up nicely as the two lovers are united and Cellini avoids death by successfully forging his statue, but it comes as a bit of an anti-climax after the earlier exuberance.

François Roussillon’s film direction deftly captures the abundance of salient dramatic points; this is quite an accomplishment.

This production opened at the English National Opera in 2014. After its Amsterdam run, it was performed in Rome, Barcelona, and Paris. I can only envy those who saw it.

Michael Johnson

|