|

Back

08/26/2013

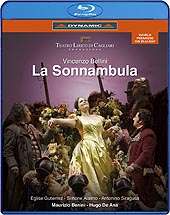

Vincenzo Bellini: La sonnambula

Eglise Gutiérrez (Amina), Antonino Siragusa (Elvino), Simone Alaimo (Il Conte Rodolfo), Sandra Pastrana (Lisa), Gabriella Colecchia (Teresa), Gabriele Nani (Alessio), Max René Cosotti (Un notaio), Coro del Teatro Lirico di Cagliari, Fulvio Fogliazza (chorus master), Orchestra del Teatro Lirico di Cagliari, Maurizio Benini (conductor), Hugo De Ana (director, set and costume designer), Paolo Mazzon (lighting designer), Leda Lojodice (choreographer)

Recorded at the Teatro Lirico Cagliari (October 2008) – 141’

Dynamic 55616 – Booklet in Italian and English – Subtitles in English, Italian, French, German, Spanish

This production from the venturesome Teatro Lirico in Cagliari, Sardinia, was filmed in 2008. Hugo De Ana’s ultra-romantic design and direction (previously seen at the Teatro Filarmonico, Verona) is meant as a tribute to the historic 1955 production of La sonnambula produced by Luchino Visconti at La Scala, Milan, with Maria Callas, conducted by Leonard Bernstein. Photos from this production show Callas dressed as if to perform the ballet La Sylphide, which is appropriate as the two works deal with romanticized rusticity and were first performed within a year of each other. It comes as no surprise to learn that Bellini’s opera was derived from a ballet.

The piece can only succeed with persuasive singers in the two lead roles. Eglise Gutiérrez as Amina succeeds splendidly; aside from singing beautifully she maintains a wonderful slightly-detached-from-reality persona throughout, with balletic port-de-bras even. Antonino Siragusa is a real tenore di grazia but he has an unfortunate habit of pushing his voice into a note from below. I started to count the numbers of times he did this but soon gave up. Pristine vocal technique (always welcome) is particularly required for Bellini. But he can float some meltingly beautiful lines - just what one wants. Probably his biggest problem is that he is not Juan Diego Flórez.

Veteran baritone Simone Alaimo does a fine job as Count Rodolfo, as does Sandra Pastrana as the inn-keeper, Lisa, who has her sights on Elvino. The comprimario roles are also strongly performed: Gabriele Nani as Alessio, Lisa’s spurned swain; Gabriella Colecchia as Teresa, Amina’s mother; and Max René Cosotti as the notary. Chorus and orchestra sound fine under the experienced baton of Maurizio Benini.

Hugo De Ana’s usual approach to an opera is to establish some sort of symbolic image that exemplifies what the piece is about. In this case it seems to be a rolling meadow; changing locales (such as the count’s room at the inn) are indicated by a few props. The props are moved around by four young men dressed as 18th-century footmen in livery; if this sounds incongruous, that’s exactly what it is. At stage rear, behind a scrim, we see an array of changing projections, including what appears to be a ballerina in white heralding the sleepwalking scenes. The second sleepwalking scene is supposed to show Amina crossing a narrow bridge in full view of the villagers; here there is ghostly movement behind the scrim and then the footmen deliver Amina on a flower-bedecked carriage. It certainly makes a pretty - and ultra-romantic - picture.

In spite of the implied naturalism of the meadow, the staging is highly stylized, especially re the use of the chorus, who adopt frozen tableaus much of the time. Their costumes are very sumptuous for “simple” villagers. The women all have the centre-parted “ballerina” hairstyle.

If I had seen this performance live I probably would have been quite pleased with it. After all, it’s an attractive attempt to present the opera in its vintage pastorale form; it is not set in a sanatarium (as was the most recent production at Covent Garden) nor in a modern-day rehearsal studio (as was the most recent production at the Metropolitan Opera. However, the work is described as “semiseria” and I could have done with less of the “seria” (it is possible to mix sentiment with laughter, as the ballet La Fille mal gardée demonstrates). Overall, De Anna’s approach is respectful to the point of becoming precious.

What diminishes enjoyment most, though, are the inevitable close-ups in a filmed production. One expects this - and the alternative, with a camera or cameras placed only at normal audience distance, would be boring. In this case, though, the close-ups magnify certain aspects that break the spell Bellini’s music can and should exert. For example, Eglise Gutiérrez wears a sparkly red and black dress in Act I, when she is meant to be a simple village girl on her engagement day. The sparkles might just add a touch of theatricality in the theatre, but up close they are out of place. Her fiancé wears a red suit with glittery lapels; as a result: they look more like Carmen and Escamillo. Later, in Act II, for awhile she wears a black cape also with sparkles, and in her final great aria and cabaletta she wears jewellery befitting a duchess. (Callas in 1955 apparently wore a sumptuous necklace during the final scene as well, but this was the era before filmed close-ups.) The camera also rather cruelly shows the tenor to be 40ish rather than 20ish. I realize it is unreasonable to expect a 20ish tenor in this role, but while sitting in row L or wherever one persuades oneself that the reasonably trim and agreeable man is in the first bloom of youth where as when confronted by the close-up the game is over. (The same problem exists re the great wave of high-definition broadcasts that now occupy a lot of music-lovers’ time.)

To sum up: this is a more-than-decent attempt to present this difficult work on its own terms. Bellinians who can overlook a few tenorial flaws should like it, and it might even win over others to the cause, especially if they are ballet fans.

Michael Johnson

|