|

Back

06/09/2022

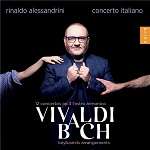

“Vivaldi - Bach”

Antonio Vivaldi: L’estro armonico, opus 3: Concerto n° 1 in D major for four violins, RV 549 [1, 2, 3, 4] – Concerto n° 2 in G minor for two violins, RV 578 [2, 3] – Concerto n° 3 in G major for violin, RV 310 [2] – Concerto n° 10 in B minor for four violins , RV 580 [1, 2, 3, 4] – Concerto n° 11 in D minor for two violins and cello, RV 565 [3, 4] – Concerto n° 12 in E major for violin, RV 265 [4] – Concerto n° 4 in E minor for four violins, RV 550 [1, 2, 3, 4] – Concerto n° 5 in A major for two violins, RV 519 [1, 2] – Concerto n° 6 in A minor for violin, RV 356 [1] – Concerto n° 7 in F major for four violins, RV 567 [1, 2, 3, 4] – Concerto n° 8 in A minor for two violins, RV 522 [1, 4] – Concerto n° 9 in D major for violin, RV 230 [3]

Johann Sebastian Bach: Concerto in F major for harpsichord, BWV 978 (after RV 310) [5] – Concerto in A minor for four harpsichords and strings, BWV 1065 (after RV 580) – Concerto in D minor for organ, BWV 596 (after RV 565) [9] – Concerto in C major for harpsichord, BWV 976 (after RV 265) [5] – Concerto in A minor for organ, BWV 593 (after RV 522) [9] – Concerto in D major for harpsichord, BWV 972 (after RV 230) [5]

Andrea Rognoni [1], Stefano Barneschi [2], Boris Begelman [3], Elisa Citterio [4] (violin), Rinaldo Alessandrini [5], Andrea Buccarella [6], Ignazio Schifani [7], Salvatore Carchiolo [8] (harpsichord), Lorenzo Ghielmi [9] (organ), Concerto Italiano; Rinaldo Alessandrini (director)

Recording: Sala Accademica del Pontificio Istituto di Musica Sacra, Rome, Italy (December 14-20, 2020) – 158’62)

2 CDs Naďve OP 7367 – Booklet in French and English

Antonio Vivaldi is widely esteemed for his Gloria and The Four Seasons, but equally memorable, though not as well known, is the collection of 12 concertos for stringed instruments, L’estro armonico, opus 3, the first set dating from 1711 when Vivaldi was 33. They represent the composer’s first venture into the concerto medium, of which he became a master, with nearly 500 surviving today. L’estro armonico (translated as The Harmonic Inspiration) had a profound influence on Johann Sebastian Bach, in his 20s when they were published, leading him to transcribe six of these concertos for keyboard instruments.

Concerto Italiano, led by Rinaldo Alessandrini, has released a two-CD album of the 12 concertos interspersed with performances of the Bach transcriptions performed by Alessandrini on the harpsichord, Lorenzo Ghielmi on organ, and Alessandrini, Andrea Buccarella, Ignazio Schifani, and Salvatore Carchiolo as soloists in the Concerto in A minor for four harpsichords and strings, BWV 1065 (after RV 580).

I have had a lifelong affection for L’estro armonico, which I discovered in the record department of Lit’s Department Store in Trenton, New Jersey, when I was working my way through college. The recording was a three-record boxed set in the Vanguard Everyman Classics series featuring a performance by the Chamber Orchestra of the Vienna State Opera, Mario Rossi, conductor, and including solos by Willi Boskovsky, a popular violinist at the time. This was during the era of the great Vivaldi revival. How could this music have been largely forgotten and downgraded for decades, even centuries? As I heard it for the first time many years ago, it uplifted mind and spirit with its stately and majestic airs, yet tempted listeners to kick off their shoes and dance.

Many years have passed, and Vivaldi remains in the top echelon of Western classical composers. Listening to this new recording by Concerto Italiano affirms that popularity, but with new insights from scholarship and popular taste. While Rossi focused on the measured dignity of the High Baroque, Alessandrini leads this ensemble at a brisk clip through the allegro movements, reflecting a 21st century penchant for speed.

But stateliness? Not so much. There is beautiful phrasing by soloists and not a little grit, yet the overall impression throughout the album is one of lightness rather than grandeur. The sound in this recording can be thin, as though the soloists and string section are too far from the microphone. Following the otherwise excellent booklet notes, it was not always clear which soloist performed in which track. The slower movements tended to have a drowsy quality, as though the artists were reluctant to move to the next measure. But the quality of musicianship was high, with few exceptions (tracks 22 and 28 in CD1, both largos, could have used a bit more energy and conviction).

The Bach transcriptions for harpsichord were particularly attractive, as Alessandrini conjured a variety of moods and textures from an instrument not given to imaginative displays of color. The last track in the album—Concerto in D major for harpsichord, BWV 972 (after RV 230)—contains some highly original phrases and startling bursts of originality in the closing “Allegro”, effects which I would have enjoyed hearing earlier and more frequently.

A valuable addition to this album and its notes would be conspicuous information about the instruments, bows and strings used in this recording. My love of the rich full sound of the modern orchestra, even when playing works from the Baroque, usually outweighs my need for the veracity of historically informed instruments. Knowing what we are listening to, and why, can only add to our understanding and appreciation.

Linda Holt

|