|

Back

04/18/2021

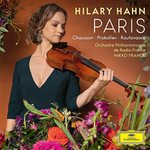

“Paris”

Ernest Chausson: Poème, opus 25 [2]

Sergei Prokofiev: Concerto for Violin and Orchestra n° 1 in D major, opus 19 [2]

Einojuhani Rautavaara: Deux Sérénades [1] ^

Hilary Hahn (violin), Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France, Mikko Franck (conductor)

Recording: Auditorium de Radio France, Paris, France (February 2019) [1] ^ World Premiere Recording, June 2019 [2]) – 52’51

Deutsche Grammophon 00289 483 9847 (Distributed by Universal Music) – Booklet in English and German

A new album by violinist Hilary Hahn is always cause for delight, and “Paris”, her latest offering, is no exception.

The album cover collage provides a warm, enchanting invitation to listen, depicting a bower of spring flowers surrounding the musician. Here is a romantic image of the Paris of our imagination, but don’t assume this album is in any way light-hearted background music.

Hahn is, after all, one of the world’s most formidable violin soloists, and while some of the moods of this album may be the stuff that dreams are made of, Hahn also presents us with interpretative insights that reveal depth and substance in works by Chausson, Prokofiev, and Rautavaara, all connected in some way to the French capital city.

Hahn is joined in this recording by the Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France (OPRF) under the direction of Mikko Franck, an ensemble with which she has had a long professional association. The album begins with Chausson’s Poème, a beloved staple of the violin repertoire. Chausson dedicated Poème to Eugène Ysaÿe, a French violinist who taught Hahn’s own teacher, Jascha Brodsky.

While orchestra and soloist play with an appropriately light touch, there is a recurring pattern of darkness as Hahn explores the inner workings of this moody tone poem. It develops like the soundtrack for a film set by the Cornish coast or a reminiscence of a country childhood by Vaughn Williams or Gerald Finzi. Hahn’s skill at manipulating runs, trills, double stops, her breathtaking lyricism, all blend in a performance of virtuoso brilliance, but at root lies a partnership with the orchestra not unlike waves eternally dancing on the shore.

The star of the album is Prokofiev’s Concerto for Violin and Orchestra n° 1 in D major who composed a score years after the Chausson work and premiered at the Paris Opéra. Hahn has long been linked to this work that alternates charm with abrasiveness. It wasn’t radical enough for French audiences in the 1920s, but it has carved a place in the violin repertoire thanks to the dedication of violinists such as Hahn. Despite its conventional scoring, it is a work of unrelenting musical interest from its beginning (with an immediate violin statement) to its anticlimactic but appealing end.

Hahn’s bow draws out the sweet sounds of some high, dancing notes, and proceeds in a manner that is both playful and cagey. Soloist and orchestra bandy a series of discords and resolutions to and fro, leaving the first movement to end in a kind of tracery by the violin’s melodic line, as though drawing lacey patterns in the snow with one finger.

The second movement is vintage Prokofiev, the kind of sparkling but assertive voice one hears in Romeo and Juliet or the Classical Symphony. A rhythmic feast engages the orchestra in the final movement, which ends with the violin soaring brightly, then seeming to whisper, “Good night!”

The album concludes with Deux Sérénades (two movements) for violin and orchestra by the late Finnish composer, Einojuhani Rautavaara, a World Premiere Recording and composed for Hahn. The violinist originally asked Rautavaara to write a violin concerto, but his ill health prevented the completion of the project. After his death, Hahn and Franck discovered two movements, nearly completed. Franck then commissioned Finnish composer Kalevi Aho, himself a student of Rautavaara, to complete the work which is now dated 2016-2018.

Those who enjoyed the Chausson tone poem at the beginning of the album will find similar food for the soul in these dreamy, nostalgic selections. Hahn’s clear and, I think, appreciative melodic line cuts through the orchestra like a ray of sunshine through friendly clouds. Again, I was reminded of the English pastoral composers, this time The Lark Ascending, though other listeners may take the view of the 1920s audience which felt lukewarm about the Prokofiev concerto and ache for sounds that are more contemporary.

Linda Holt

|